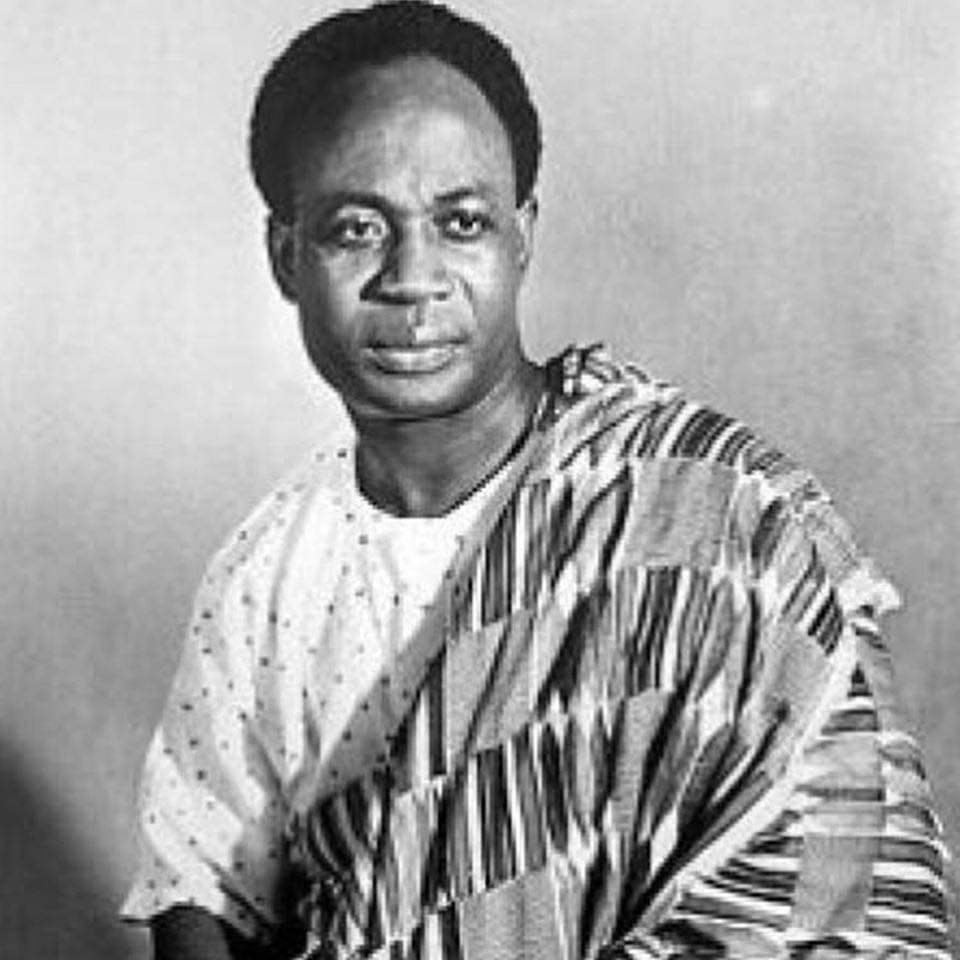

“What we need is confidence in ourselves, so that as Africans we can be conscious, united, independent and creative. Knowledge of African achievements in art, education, religion, politics, agriculture, medicine, science and the mining of metals can help us gain the necessary confidence which has been removed by slavery and colonialism.”

Walter Rodney

HOGAN'S ALLEY AND FOUNTAIN CHAPEL

Remembering the historical significance of Strathcona, Fountain Chapel and Hogan’s Alley.

DIASPORA INITIATIVE

At AGL we successfully engage our partners and stakeholders, get to know them, promote a good understanding of their background.

Celebrating African Heritage with Kwanza and Black History month to recognize, promote and celebrate African Cultural Heritage.

HOGAN'S ALLEY

A 1957 study by the City of Vancouver Planning Department described the black population of Strathcona as such: “The Negro population, while numerically small, is probably a large proportion of the total negro population of Vancouver. Their choice of this area is partly the proximity to the railroads where many of them were employed, partly its cheapness and partly the fact that it is traditionally the home of many non-white groups.” 2016 Africa Great Lakes Networking Foundation with other African-black peoples local and international organizations have planned to Celebrate the 100 years of Fountain Chapel Vancouver, with different activities that will see people from all walks of life participate.

Hogan’s Alley was the local, unofficial name for Park Lane, and alley that ran through the southwestern corner of Strathcona in Vancouver, British Columbia during the first six decades of the twentieth century. It ran between Union and Prior Street from approximately Main Street to Jackson Avenue. While Hogan’s Alley and the surrounding area was an ethnically diverse neighbourhood during this era, a home to many Italian, Chinese and Japanese Canadians, a number of black families, black businesses, and the city’s only black Church, ![]() the African Methodist Episcopal Fountain Chapel, were located here. As such Hogan’s Alley was the first and last neighbourhood in Vancouver with a substantial concentrated black population. A possible reason these families settled there was that of the close proximity to the train stations since sleeping care porters were predominantly black men.

the African Methodist Episcopal Fountain Chapel, were located here. As such Hogan’s Alley was the first and last neighbourhood in Vancouver with a substantial concentrated black population. A possible reason these families settled there was that of the close proximity to the train stations since sleeping care porters were predominantly black men.

Close to BC’s oldest residential and truly unique neighbourhood lays the local chapter of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) also known as Fountain Chapel located at 823 Jackson Avenue from 1918 until 1985. The AME was co-founded by Nora Hendrix (grandmother of guitarist Jimi Hendrix) to serve Vancouver’s black community. Prior to the establishment of the Fountain Chapel, black Christians held services in rented halls around town, and eventually, a small group decided they should have a permanent church of their own. They set out to raise funds for the project and arranged for the AME to match the amount reside locally. Once financing was secured, , they purchased the building on Jackson Avenue that was built in 1910 and had served as a Lutheran Church for German and Scandinavian immigrants.

The AME is a well established Christian denomination that was founded in 1816 by African Americans in response to the racism they encountered in non-segregated churches, AME was an important institution for black opposition to antebellum slavery and anti-black racism generally.

The AME is a well established Christian denomination that was founded in 1816 by African Americans in response to the racism they encountered in non-segregated churches, AME was an important institution for black opposition to antebellum slavery and anti-black racism generally.

AFRICAN DIASPORA

At AGL/GL-BC, we believe that true impact begins with meaningful relationships. We work closely with our partners and stakeholders to understand their backgrounds, listen to their experiences, and recognize their unique personalities. Whether through face-to-face meetings, phone calls, or a simple email, we prioritize using communication tools that make people feel comfortable and valued. By investing in knowing each stakeholder well, we are able to design project plans that promote our cooperation, strengthen engagement, and advance our shared objectives.

We are committed to ensuring that the needs of our communities and stakeholders are not only heard but acted upon. Whether serving a small group within a larger enterprise or addressing the concerns of an entire community, we focus on delivering solutions that work, especially for underserved populations/interfaith minorities and social enterprises.

At the core of our approach is community collaboration. We take ownership of our projects by mastering every detail, from scope and deliverables to milestones and outcomes, while keeping communities at the center of decision-making as well. We organize, listen, and engage directly, creating safe platforms where voices are heard and respected, inviting feedback, explaining our purpose with transparency, and ensuring that communities see themselves not just as beneficiaries but as partners in shaping the programs that affect their lives.

This inclusive, participatory approach ensures that everyone feels recognized, useful, and part of the solution. It creates a sense of belonging, community and shared ownership, which is the foundation of resilience and sustainable change. Guided by past experience and grounded in current realities, we remain responsive and flexible, always listening first, then acting together.

Through this model, we do not simply implement programs; we build trust, nurture hope, and empower communities to lead the way toward long-lasting impact locally, nationally and globally.

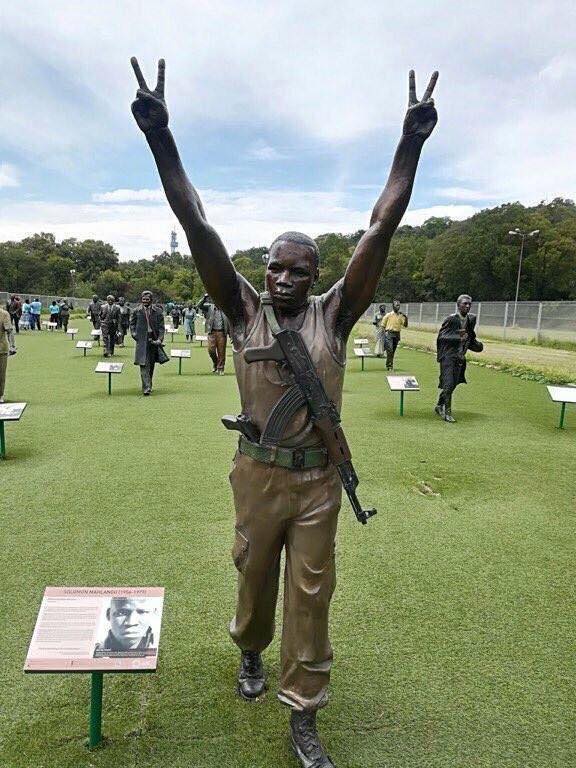

AFRICAN HISTORY

Celebrating African Heritage Beyond February

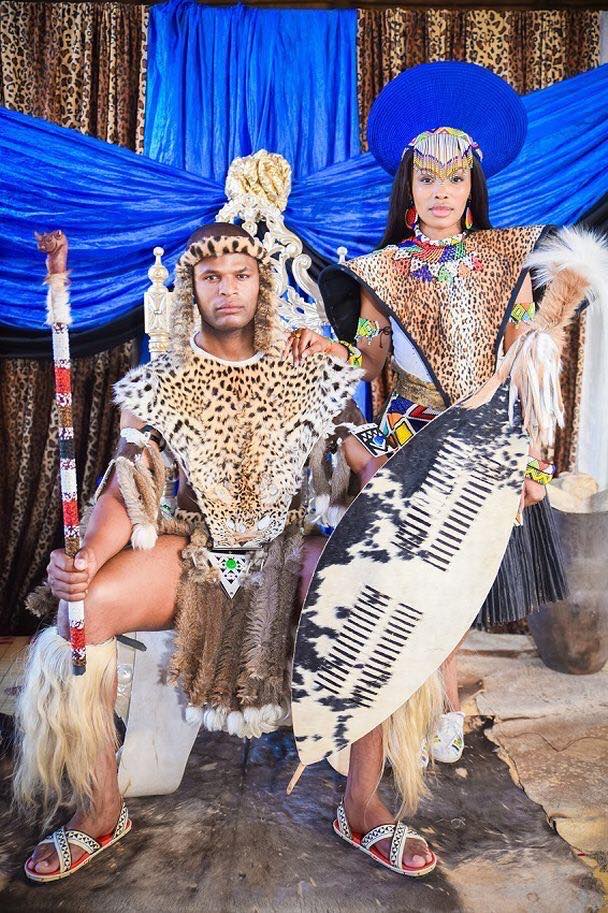

At GL-BC, we believe that Black History is more than a single month—it is a living legacy that must be celebrated year-round, that is the reason why at GL-BC, we celebrate Black History Mashujaa Beyond Febuary. Through Canada–Africa Week and Kwanzaa celebrations, we recognize, promote, and honor African cultural heritage, traditional values, customs, beliefs, family, community, and languages.

Our work focuses on educating children and youth to appreciate the richness of African history, culture, and identity as a way to counter negative racial stereotypes and institutional racism that we continue to witness. By sharing African history, heritage, and stories, we place emphasis on the strength, creativity, and resilience of Black/African peoples rather than narratives of deficit or struggle. We encourage children to celebrate both their mother’s and father’s sides of heritage, understanding that one is not greater than the other, but together they form a rich identity to be proud of.

Learning about the past equips the next generation with the tools to recognize their ability to overcome the lasting legacies of racism, legacies that are still visible today in income, health, housing, and education disparities. Connecting young people to their roots helps ensure they remain proud of their history, cultures, and ethnicity while building resilience and confidence for the future.

Through community celebrations, storytelling, music, dance, food, and language, we highlight the joy and beauty of African culture. These moments bring families and communities together to reaffirm identity, promote unity, and inspire hope. By celebrating heritage, we remind ourselves and our children that African culture is not only about survival, but, it is about thriving, belonging, and passing on wisdom to future generations.

The Many Myths of Slaves and the Underground Railroads

The Underground Railroad: A Path to Freedom

The Underground Railroad was the largest anti-slavery freedom movement in North America, helping between 30,000 and 40,000 enslaved African Americans escape to freedom in British North America (Canada). It was not a railroad, but a secret network of people, safe houses, and routes that brought hope and dignity to those fleeing enslavement in the American South.

Origins and Growth

Freedom in Canada became possible after the 1793 Act to Limit Slavery declared that any enslaved person who reached Upper Canada was free. After the War of 1812, word spread that “Black men in red coats” lived freely in British North America. Arrivals increased dramatically after the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act, which allowed slave catchers to pursue fugitives even in the Northern states, forcing many to seek refuge in Canada. The Underground Railroad began in the early 1800s, organized by abolitionists in Philadelphia. By the 1830s, it had become a dynamic, clandestine network. Using railroad terms as code, fugitives were called “passengers,” safe houses were “stations,” and guides were “conductors.”

Heroes of the Movement

The Railroad was sustained by a diverse group: free Black people, former slaves, White allies, Quakers, Indigenous supporters, clergy, farmers, women, and urban residents. Harriet Tubman, one of the most famous conductors, personally guided dozens to freedom. Station masters offered fugitives food, shelter, clothing, and protection, often risking their own lives. Black leaders such as William Still in Philadelphia and Jermain Loguen in Syracuse were instrumental, while women like Lucretia Mott, Laura Haviland, and Henrietta Duterte also played key roles. Ticket agents” coordinated safe travel, sometimes using their professions—preachers, doctors, or travelers—as cover. In Canada, Dr. Alexander Milton Ross spread the word in the South while pretending to birdwatch, quietly equipping people for escape. Many others supported as “stockholders,” donating money or supplies.

Dangerous Journeys

Escape routes, called “lines,” stretched across 14 Northern states into Upper and Lower Canada. Travelers followed the North Star (“the drinking gourd to guide their way. Journeys were perilous: many walked for weeks at night, hid during the day, or were smuggled in wagons, carriages, boats, and sometimes trains. The end of the line was “heaven” or the “Promised Land -Canada”.

Arrival and Legacy in Canada

Between 1850 and 1860 alone, 15,000–20,000 fugitives arrived in the Province of Canada. They settled in Niagara Falls, Chatham, Windsor, Hamilton, Toronto, and beyond. Despite bounty hunters occasionally crossing the border, freedom-seekers built new lives, founded schools and churches, and contributed to Canada’s social, cultural, and economic development. Communities such as Buxton and Sandwich became centers of Black resilience and achievement. One well-known story tells of Joseph Alexander in Chatham, Ontario. When his former enslaver came to claim him, the local Black community gathered in solidarity, refusing to let him be taken. Alexander chose freedom, a symbol of the collective determination to protect one another.

Why It Matters Today

The Underground Railroad was more than an escape route—it was a movement of courage, solidarity, and resistance. It united people across race, class, and geography in the pursuit of justice. In Canada, it shaped strong Black communities whose descendants continue to enrich the nation. Remembering the Underground Railroad reminds us that freedom, equality, and human dignity are values worth protecting. Its legacy challenges us to continue confronting racism and discrimination, while celebrating the resilience and contributions of those who sought—and secured—freedom on Canadian soil.